My volunteer stint at Save Vietnam’s Wildlife (SVW) began with a baptism of fire. It was a Sunday afternoon and I had been eating lunch at the sleepy village restaurant with a couple of other volunteers when SVW’s director Thai cruised past on his motorbike. They were going to rescue 22 pangolins that had been found smuggled in the boot of a car in nearby Ninh Binh city. Did we want to come? Ummmm, yeah we did! We raced home to put on our ‘Save Pangolins’ t-shirts and load up a minibus with wooden pangolin crates.

But wait – what actually are pangolins, you ask? Only the strangest and greatest creatures you’ve never heard of. They’re mammals covered in keratin scales, giving them a primitive, reptilian look. They lick up ants with a tongue as long as their body. They roll into a ball when threatened. Which worked out really well for 60 million years until humans came along, shrugged, and threw them in a bag. These improbable creatures are now the most trafficked mammal in the world, critically endangered because their meat is considered a delicacy and their scales are used in traditional medicine.

At this point in time, however, I’d only been at SVW for two days and I had never even seen a pangolin before, so I had no idea how I’d contribute to the rescue. We parked in a courtyard and were led to a garage by government officers in military green uniforms. Inside was a giant cane basket. Inside that were lots of smaller bags. I blinked, trying to adjust to the dim light. And then an otherworldly eye blinked back at me through the gauze of a bag. I had mentally prepared myself for upsetting scenes of animal suffering, but something about seeing them packed in bags like groceries really hit me.

A pangolin peers out of a bag at the rescue. Photo by Sofiya Shukhova.

Confronting though it was, we had to get to work. We took the pangolins out of the bags, gave them a basic medical check, weighed them, put them in dark wooden boxes and feed and watered them. I had been worried I’d be a useless bystander, but I was assigned the job of giving the animals an ID number and recording their weight and sex. Soon numerous people were calling out figures for me to record, often at the same time. It was boiling hot. I sweated and scrawled like my life depended on it.

Pangolin weigh-in. Photo by Sofiya Shukhova.

A pangolin gets some water. Photo by Sofiya Shukhova.

Afterwards, we were invited to have tea with the government officers. This involved much beer, smoking and laughter. The officer across from me vigilantly refilled my cup of strong Vietnamese green tea and motioned for me to eat more lychees if I displayed any signs of slowing down. The officer in charge was evidently impressed with the work we’d done with the pangolins, because the paperwork to release them into SVW’s care was fast-tracked. At other times, this bureaucratic process can take multiple days, resulting in the death of already-weak animals that desperately need access to proper care after long journeys on the trafficking route.

On the way home, we didn’t talk much. I was hot and exhausted. But I was also depressed. Did these creatures snuffling about in the boxes behind me have any inkling of the fate they had just evaded? I knew I should be elated by their rescue, but instead my heart hardened a little like a callous. I was frightened by the insatiable, zombie-like manner in which humans were devouring the world’s creatures. Lying under my mosquito net that night, I hated on my species in an unhealthy way until I fell asleep.

The fact is that the animals we had rescued on that day were just the tip of the iceberg – lucky enough to be discovered. Wildlife is being decimated in Vietnam. Hunting and snare trapping is rife throughout many of Vietnam’s forests. In 2010 the last of the country’s Javan rhinos was killed for its horn, despite a major conservation campaign. Pangolins may be next on the chopping block, and virtually nothing is known about how many are left and where they are. In truth, they could be even closer to extinction than we realise. The pangolin trade is booming and the street value is skyrocketing. It’s not cheap. But wild meat of any kind is considered a status symbol, and is particularly popular with the upper-echelons of Vietnamese society.

Vietnam is also a huge player in the international illegal wildlife trade. All kinds of animals and animal products from Cambodia, Laos, Thailand all the way to Indonesia and Myanmar and even Africa, are funnelled through to Vietnam, either to supply the market there, or in many cases to end up in China. This modern-day ‘silk road’ is hidden from the public eye but it is sucking the life out of forests across Asia. It is responsible for much of the elephant and rhino poaching in Africa, too, and as pangolins become harder and harder to find in Asia, the crime syndicates are turning their gaze to the four species of African pangolins.

Trafficked live pangolins saved from ending up on a dinner plate.

Enforcing laws against wildlife crime is a big challenge in Vietnam. First of all, many of the laws are weak and don’t act as a strong enough deterrent. Mind-bendingly, only a few years ago it was legal for confiscated wildlife to be sold straight back into the black market by government officers after being confiscated from smugglers. Thanks to campaigning by SVW, this is no longer allowed.

The other problem is that the laws that do exist aren’t strongly enforced. An undercover journalist for CNN recently found pangolin meat openly available at a Vietnamese restaurant (at an eye-watering cost of $1,750 USD). From what I heard, this sort of thing was not uncommon. When a few of us decided to go into the nearby town for dinner one night, Thai warned us not to eat at a restaurant that served wild meat. This wouldn’t be a good look for SVW volunteers.

SVW is working to end the illegal wildlife trade in Vietnam, but it has to walk a tightrope between achieving conservation goals and keeping the government onside. Government-approval is required for them to be able to rescue animals and look after them at their centre. Their rescue centre is jointly operated with the government-run national park. The organisation has make sure that when they suggest changes to anti-trafficking legislation or rescue and rehabilitation procedures they do it in a diplomatic and constructive way, rather than being overly critical. As director of the organisation, Thai has to do a fair bit of schmoozing with government. Copious shots of rice wine are the key to strong working relationships and agreements in Vietnam, so like it or not, you have to sacrifice your liver as part of your professional duty.

Networking Vietnamese style. AKA beer and sugarcane juice after work.

SVW also has to operate in an environment in which corruption is rife. Government officials involved in wildlife confiscations are not always squeaky clean. For example they might record fewer rescued animals than there actually are, selling a few for their own benefit.

As for my daily life at the SVW centre on the edge of Cuc Phuong National Park, it was simple and absorbing. I emptied out the animals’ poo-buckets, scrubbed bowls, swept and carried in clean water. Sometimes, after I’d finished cleaning out the pangolariums, Hoi An the binturong would amble out of his sleeping box to the front of his cage. I fell in love with him, maybe partly because he smelled like buttered popcorn (the urine of binturongs contains the exact same compound). Looking like an oversized drop-bear, he’d claw and pounce at the grass balls containing banana, rolling about gleefully and beseeching me to come join in with his mischevious eyes. It was irresistibly captivating but I knew I was anthropomorphising him and he’d probably maul me with his sharp fangs if he got the chance.

Hoi An being ‘enriched’ by a ball of grass with banana inside it.

Every night as I walked back from dinner in the village, thousands of fireflies blinked from amongst the trees. Giant multi-coloured moths turned up on my bathroom wall at night. On the weekends, the staff took me to see local sights and taught me to cook Vietnamese recipes.

Banana pancakes, Vietnamese style. Delicious!

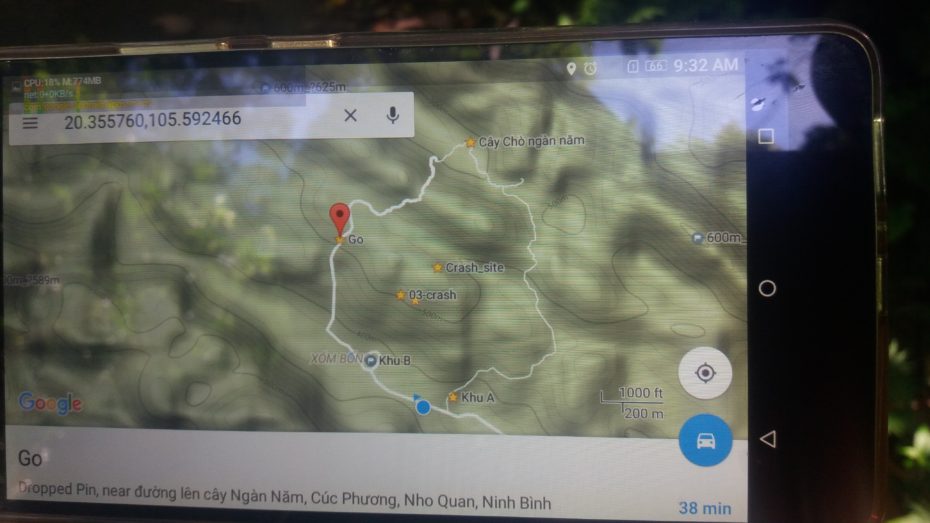

On one memorable occasion we trekked through the rainforest in search of a lost drone, tripping over, getting scratched by razor-sharp vines and running concerningly low on water. We found the drone, but under attack by vicious wasps, abandoned the search for the iPhone that had been strapped to it.

The map guiding our drone search in the rainforest.

The only view from inside the rainforest.

But volunteering at an animal rescue centre isn’t all about rainforest adventures and hanging out with cute animals. Days often involved slaving away in 50-degree apparent temperature conditions and scrubbing animal shit off bowls whilst sweat dripped off my face like I was a limestone cave feature. I felt extremely unglamorous. I got (multiple) stomach bugs. Some days I felt faint and dizzy. I definitely had moments where I wondered why I was doing this. What did I, an office-worker with a documented intolerance of extreme tropical conditions, hope to achieve here?

Scrubbing water bowls for the Owston’s Palm Civets.

I’d decided to volunteer with SVW on a whim – I was inspired by what they were doing but beyond that had little idea of what I might get out of it. Back in Australia, I had been working on conservation from behind a desk for so long that I’d started to feel disconnected. Here at SVW, the manual work was fairly monotonous, but I also felt a sense of satisfaction from the realness of it – from being able to see and feel how I was making a difference. I started to appreciate the hard work that goes into ground-level conservation. And just by being there and observing and absorbing, talking, listening to conversations over our daily team lunches, I learned.

After a stellar attempt digging for worms to feed the Owston’s civets one very hot afternoon, in which I displayed poor upper body strength, caught two worms in three hours and scowled a lot, I was gently encouraged to start helping out in the office after lunch. And thanks to my mad public servant skillz, I was able to help out with some grant applications and the drafting of a strategic plan for the organisation, so I started to see how things all fitted together. But I wasn’t naïve about my role at SVW, either. I was helping out and my presence was clearly valued by the team, but I wasn’t there for the long haul and I was also contributing to the organisation’s pretty tight budget as a paying volunteer. I felt like it was a fair trade.

In the end, the most valuable part of my two months with SVW was renewing my energy and optimism for conservation. I hadn’t realised it, but I’d started to run dry. Like an emotional vampire, I was soaking up the commitment and passion of the team at SVW.

As it happened, I had a Canberra connection with Thai, the director of SVW. He grew up in the local area around Cuc Phuong National Park but got a scholarship to study at the Australian National University (ANU) just as I moved to Canberra. We probably crossed paths at the bus interchange. When Thai wasn’t studying, he was working multiple jobs to save up money. He described how one week he worked so many hours he only had 44 left over for sleep, eating and travel. But it was worth it, because the money he saved allowed him to start SVW in 2014.

Thai seemed to work constantly, often taking visitors or film crews around the centre over the weekend, or working at his laptop late into the night. Despite being the director, he always knew what was going on with each individual animal. A few days after my first rescue, I watched him checking on a pangolin that hadn’t been eating, lifting it gently out of its sleeping box and placing it directly on a live ant nest where it finally uncurled and started to eat.

Thai checking an animal at a pangolin rescue. Photo by Sofiya Shukhova.

The dedication of the staff Thai has recruited to work with him was also palpable, and despite the fact that many of them are young and well-educated and could earn more money elsewhere, they instead choose to work in a small village in a forest where the power frequently cuts out and the water periodically stops running. They do it out of love.

The SVW team.

In my last week at SVW, we received word that around 40 pangolins had just been confiscated, but they were all headed to a government rescue centre in Hanoi. I was outraged. Why weren’t the pangolins coming to SVW, which has a proven track record in returning pangolins to good health and releasing them back into the wild, despite the notorious difficulty of keeping the species alive? Pangolins die very easily in captivity due to stress and digestive problems, and only a handful of zoos around the world have managed to keep them alive longer than six months. Less than ten pangolins have ever been bred in captivity, so release back into the wild is also crucial so that they can breed and avoid extinction.

Government-run wildlife rescue centres in Vietnam have traditionally been like a Hotel California for pangolins. Of the hundreds of pangolins sent to these centres, none were ever released back into the wild. Which raises questions. It may well be that they simply don’t have the skills or knowledge to care for this species properly. But there’s also the fact that a pangolin is worth a lot of money, dead or alive.

After the news of the latest confiscation, Thai became glued to his mobile phone. For days his phone was constantly going off, and he spent hours arguing the case for SVW to take the pangolins. Explaining, reassuring, assuaging. And after three days, miraculously, he achieved a breakthrough. SVW would be allowed to take half of the pangolins. But even better, SVW would send its head keeper, Hung, to show the government rescue centre how to look after the other half of the pangolins. Best of all, SVW would lead the first ever pangolin release from a Vietnamese government rescue-facility.

My last couple of days at SVW were exhausting, working long days and late into the nights. We received the 20 newly rescued pangolins. Normally shy but inquisitive, intrepid little creatures, some arrived at the centre with life fading from them – limp, desperately dehydrated and too exhausted to even be afraid of us. I wrote up notes until the early hours of the morning as the vets conducted health checks, tended to wounds and administered medicines.

Preparing the pangolins for release late at night.

At the same time, we were preparing to release 19 of the 22 pangolins we’d rescued when I first arrived two months ago. They had recovered their strength and were ready to make the long journey to their new home in the wild. It was 4 AM in the morning by the time the pangolins were safely in their boxes and ready to go. I couldn’t wait to go home and sleep. Meanwhile, the tireless SVW staff were about to begin a 70-hour round-trip on bumpy roads and one long night carrying the pangolins deep into the forest in treacherously slippery, muddy conditions. The trenches of conservation can really crush your spirit some days, but on that particular night, I could see that this fight could still be won. That night, the lows were easily outweighed by the inspiration of working alongside such extraordinary people.

What it’s all about. Lan releasing a pangolin back into the wild.

You can find out more about Save Vietnam’s Wildlife, including how to donate, here.