A few days after leaving Vietnam I found myself in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Something in my bathroom was leaking a clear fluid (hopefully clean water) all over the floor, and Don, the American expat-owner of my guesthouse, who had lived in Cambodia for 20-odd years, was hunched over the toilet trying to fix it. We got chatting, and I innocently mentioned my recent volunteer work with Save Vietnam’s Wildlife (SVW), a wildlife rescue centre and conservation non-profit working to stop the illegal wildlife trade. ‘They do a lot of work with pangolins – I’m not sure if you’ve heard of them?’

‘Oh-ho-ho, I know pangolins,’ Don chuckled darkly. ‘They used to be everywhere. They’d sell them at the Chatuchak markets in Bangkok. You used to be able to buy them at the markets here in Siem Reap for next to nothing. Now they’re gone.’ Don sounded angry – verging on accusatory. I made inadequate, empathetic sounds, but I had unleashed something in Don that would not be repressed.

Thus began a 20-minute tirade about on how Cambodians were killing everything wild. The giant tokay geckoes with their distinctive mating calls were gone from the balmy Siem Reap nights. Anything that flied or crawled was snaffled up to be sold for a few dollars at the local markets. The slow lorises were gone. The turtles were disappearing. The fish were being fished to oblivion. The toxic shrimp farms were destroying the waterways and the mangroves were all knocked down. The forests were being cut down, with the kickbacks from the timber concessions making millions for politicians. ‘Everything is gone. It’s too late. It’s over. I’ve seen it in front of my own eyes’. Don shook his head despairingly.

It wasn’t a completely inaccurate assessment. I’d seen for myself the piles of wild-caught snakes of varying colours and patterns being sold in the Siem Reap markets. Tarantulas harvested from the wild were sold live by the bagful to be fried up. It mirrored what I’d seen in Vietnam and what was happening all over Asia. It was a mass extirpation – almost a war on life itself.

Snakes for sale at the Phsa Leu markets in Siem Reap.

But something about Don’s tirade irritated me. A lot. In part, I objected to the way it seemed to be directed exclusively at Cambodian people as if they were uniquely ignorant and thoughtless. But historically, wealthy countries have done the exact same thing to their forests and wildlife. It’s just that they got most of the killing and destruction out of the way before there were any international conventions or conservation non-profits to criticise them for it. And before global population growth put the consumption of natural resources into steroidal overdrive.

Conservation is taken relatively seriously in first-world countries today, but in Australia in the 1800’s and right up until the mid 1900’s we waged a campaign of extermination on our native mammals, with most state governments putting a price on the scalps of all kinds of wallabies, rat-kangaroos and other marsupials. Millions and millions were hunted and killed, and for some species that was the end of the line. The Australian bush is a different place now to what it once was. Though many species have managed to hang on, and some even to thrive, the effects of organised mass-hunting were compounded by massive land-clearing, the introduction of competing grazers in the form of rabbits, and an incredibly destructive predator – the fox. Not to mention feral cats. Many of our most unique and beautiful species are at real risk of extinction in Australia. Our conservation challenges back home are often the result of past mistakes that are now impossible to reverse. Though we could hardly claim that we’re in the enlightened state in Australia where every development decision puts the survival of threatened species and ecosystems first, either.

The Tasmanian Tiger was hunted to extinction; this is a photo of the last wild animal to be killed, taken in 1930. Photo by Unknown. Public Domain.

So Cambodia isn’t the first country to suck the living daylights out of its environment, but it’s sure making up for lost time now. The truth is that a lot of people in Cambodia are really poor and they’re not educated about the importance of protecting wildlife. Don wasn’t wrong about that, despite his neo-colonialist overtones. But his outburst was still enraging me. What exactly was he doing about this if he cared so much? Why was he directing all this anger at me like he wanted to extinguish my hope? Why the mansplaining when I’d already told him I work in conservation, and thus might not need to have the declining trend for global biodiversity clobbered into me for twenty minutes?

Don talked like conservation efforts were futile. But I knew otherwise. I knew that even if species disappeared from large areas, as they inevitably do when urbanisation ramps up and farmland and plantations expand into forest, wildlife could still be protected if large enough areas of habitat remained. In Cambodia, large swathes of national park still protected some forests in remote areas where accessibility limited poaching. A community-based eco-tourism project in the Cardamom Mountains was transforming a local community from rampant poachers to staunch advocates for the environment. There were even plans to re-introduce tigers to the remote eastern plains of Cambodia.‘Well, we still have to have hope’, I ventured unconvincingly, completely failing to articulate any rationale for my optimism. Don directed his maximum scorn levels at me. ‘Hope? Hope does nothing – it’s just naivety’, he snarled.

A community-based ecotourism project has been set up in Chi Phat, Cambodia. Photo by Axel Drainville. CC BY-NC 2.0

I tried to exercise compassion. This emotional break-down taking place on the bathroom floor was Don’s way of expressing his grief at a mass global extinction event. Any human being who holds even a modicum of concern about the planet will occasionally feel freaked out by the rapidly accelerating losses and the ever-ticking clock. Working in conservation, I knew this fear intimately. I dealt with it day-in, day-out. Environmental work can take a heavy toll on your spirit – and even your mental health. You can become very cynical and critical and focus on the negative.

But during my time with SVW, helping to protect wildlife from the illegal trade, I had come face to face with my own cynicism and negativity. And I had realised it wasn’t helping me. Or the planet. It might sound new-agey, but I realised that what I actually needed was to make more mental space for gratitude. For what we still do have. For working with passionate, inspiring people. For the fact that there’s still some time and that human society can change rapidly when the right levers are pulled. That we still have beautiful places and wonderous creatures to protect.

And I started to appreciate some of the positives back in Australia. Things are a long way from perfect, but conservation projects can get funding from the government. Environmental issues receive a lot of public attention. People by-and-large get to spend time in nature, value it and respect the rules that protect it.

By and large, people are connected to the natural environment in Australia and value and respect it. Photo via Good Free Photos.

In contrast, many countries don’t have enough rangers to protect national parks properly, and the rangers that are employed might be apathetic or corrupt. In many parts of the world, there aren’t really any conservation grants from the government. Conservation projects rely largely on international donations. For many city-dwellers in the world’s blossoming metropolises, real nature is just an abstract concept. In Vietnam, a big part of SVW’s work is bringing kids to the national park to see and learn about nature in real-life. As Lan, the education officer stressed, how can people be expected to love and protect something they’ve never experienced?

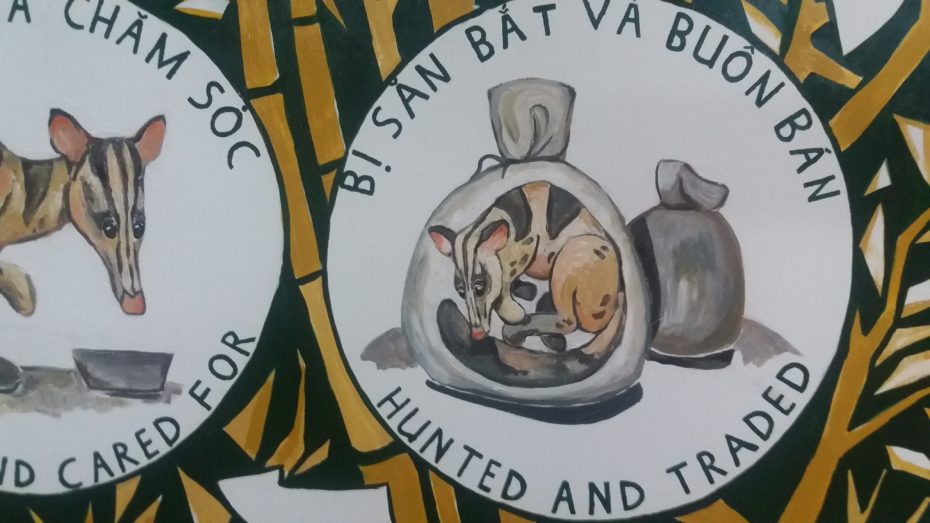

A mural in the education centre at SVW to connect kids with threatened wildlife.

And yet somehow, in spite of all these challenges, at Save Vietnam’s Wildlife optimism reigned, at least most of the time. At meetings under a shady tree outside the office I listened as the team hashed out their strategy for the next few years, fully aware of the challenges they faced, but determined to keep changing things for the better. Every time the laws were tightened to protect wildlife, it was a win. Every time the government bowed to pressure to improve wildlife crime enforcement, it was a win. When the international CITES meeting agreed to ban trade in all eight species of pangolin after years of campaigning, it was a win. I really learned something about resilience here. About being constructive instead of cynical. Patient instead of frustrated. Not out of denial of the scale of the problem or out of naivety but out of pragmatism.

In our living history, humans have already orchestrated the last footsteps of many species. There is no doubt that we will lose the battle to save many more. Our climate is changing. Our population is growing and we are ravenous. But this is no excuse to throw in the towel. There’s still so much beauty in this world that is worth saving. And I truly believe there’s a decent chance we can still turn our human juggernaut around. The giant panda has just been taken off the ‘endangered’ list – down-listed to the less dire ‘vulnerable’ status. We nearly hunted some whale species to extinction, but today their populations are recovering. In my hometown of Canberra, species long extinct from mainland Australia are being successfully reintroduced in predator-proof reserves.

The Eastern Quoll has been extinct on the Australian mainland since the 1960s, but is now being reintroduced at Mulligans Flat Woodland Sanctuary in Canberra. Photo by David Jenkins. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

What we do today will determine what humankind still has to treasure and wonder at and worry about in the future. The one thing Cambodia, Vietnam, Australia and the whole rest of the world can’t afford to do right now is to get stuck wallowing in our own hopelessness and apathy just at the very time we need to be throwing our best efforts at global conservation. It’s not over until the final curtain call. Until then, there is only enough time to focus like a laser on ambitious but achievable goals and work away at them. Dons of the world, I get where you’re at, but I’m like, five steps ahead of you. I’ve been through the anger, grief and hopelessness and I’m now sitting at constructive action and optimism. So bitch do NOT kill my vibe.

At this point in human history, whether you work in the environmental field or whether you’re just a concerned citizen, mental strength and resilience are required. Time is not on our side. There can be no guarantee of success. But hope is critical to our mission. So take your protein pills and put your helmet on. It’s going to be a bumpy ride.