‘They have so little but they’re so happy!’ I’ve heard this so many times from fellow travellers. The inference usually being that local people in the country they’ve visited are much happier than us stressed-out, time-poor and anti-depressant-popping westerners. I know it comes from a well-meaning place, but this statement makes me feel really uneasy. I’m going to try and explain why, hopefully without sounding like an extremely annoying and moralistic person.

When we travel, it’s true that we often see beautiful smiles and hear joyous laughter in developing countries that could easily give the impression of people who are very happy. But as short-term visitors I wonder whether our superficial observations give us enough insight to really comment? In many cultures celebrating visitors and showing hospitality and kindness is extremely important, but the beaming smiles, singing and dancing and laughter don’t necessarily reflect what we know as ‘happiness’. The same people may still have serious problems that they worry deeply about in private.

This lady we met in Timor-Leste had a beautiful smile. Whether she is very happy or not, I don’t know!

When my Mum and I visited the Mekong Delta, our young tour guide had a gorgeous smile and a very happy demeanour, but at the end of our trip when we invited her to eat lunch with us and asked her about her life, it turned out that her circumstances seriously limited her choices and heavily burdened her. She worked a full time job as a tour guide but still had to do all the cooking and cleaning for her husband’s extended family whom she lived with. She dreamed of getting a better education and wanted to save money to study at university, but she had to hand over a large proportion of her wages to her mother-in-law instead. She wished for a very different life, but this wasn’t something that she necessarily declared openly to tourists.

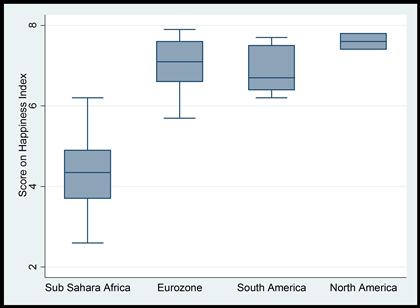

The 2016 World Happiness Report confirmed my suspicions about the ‘poor but happy’ idea. As it turns out, it’s quite simple. The rich countries are the happiest. Scandinavian countries are among the happiest in the world. Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are the least happy.

There’s also this map showing how rates of depression compare globally – you can see that clinical depression is actually more prevalent in most developing countries. Unsurprisingly, countries affected by conflict seem to have particularly high rates of depression, e.g. Afghanistan and Iraq. Unfortunately the poorest countries also tend to lack mental health services and mental illness is often a major taboo, with sufferers stigmatised by communities who lack awareness of mental health issues. For example in Guyana, the South American nation which reportedly has the highest suicide rates in the world, mental illness is often mistakenly attributed to witchcraft.

Whilst average happiness is strongly correlated with the wealth of a country, it’s not a totally linear thing. There are lots of other factors that can make a significant difference, too. On the World Bank End Poverty blog, Tom Bundervoet found that Malawi is one of the happiest countries in Africa, despite 74% of people living in poverty, whilst Togo is the least happy, despite *only* 39% of the population living in poverty.

Likewise, I realise that just because a country is rich it doesn’t mean it’s all rainbows and butterflies for its citizens. High average happiness levels in rich nations can mask high rates of depression and suicide. In a TED Talk on the dark side of happiness, Meik Wiking from the Happiness Research Institute explains how exposure to other people’s happiness can actually have a negative impact on our own happiness. This is known as the suicide-happiness paradox, where happier countries actually have higher suicide rates. It’s thought that this is due to social comparisons – if you feel you’re the only unhappy/unemployed/poor person it’s much harder to face.

So there are clearly lots of cultural and historical and social factors that affect happiness apart from simply the level of wealth that a country has. But we shouldn’t underestimate the impact of poverty on happiness, either. Despite the unaccountable happiness of Malawians and the seemingly unjustified misery of the citizens of Togo both nations are still a lot less happy than the average wealthy nation.

Source: World Database of Happiness

So western travellers might be massively over-simplifying things when we say that poor people are ‘so happy’. But I think we probably do this because we sense people in developing countries have something that we feel has been lost from our affluent, comfortable societies. Something that isn’t happiness, but might easily be mistaken for happiness at first glance….

Research published in Psychological Research helps to illuminate the weird paradox that’s going on here. Basically, people living in poor countries are far less happy and satisfied with their lives, for all the reasons you’d expect – people do not particularly enjoy living in poverty and they wish for better lives.

But at the same time, people in poor countries report much higher levels of meaning in their lives. Whilst 95 to 100% of respondents in Sierra Leone, Togo, Kyrgyzstan, Chad, and Ethiopia said they lived a meaningful life, only two-thirds of those in Japan, France and Spain felt their lives were meaningful.

So what’s going on here? Well, people in poor countries derived this sense of meaning largely through religion and spirituality, strong social connections and the satisfaction of raising their children (countries with a higher fertility rate reported higher levels of meaning). Though we might not all feel that religion and child-rearing are the purpose of life, we can probably agree that western societies lack a sense of higher purpose, strong family-life and community-connectedness.

Father and son in Com, Timor-Leste.

This article in the Scientific American describes a survey of almost 400 Americans, which found that a happy life and a meaningful one are not necessarily the same thing. Happiness is correlated with a pleasant, easy life largely free from sickness and trauma. It is associated with spending time with friends, and it is also correlated with money. Maybe money can buy happiness after all?

Meaningfulness, on the other hand, was correlated with spending more time with loved ones (as opposed to friends), giving to others, being able to express, understand and define yourself and doing routine activities such as cooking, exercising, cleaning, praying and meditating. Interestingly, though it’s common advice to ‘live in the moment’, meaningfulness is actually associated with linking the past, present and future into a big arc – not just focusing on being happy in the present.

We all derive meaning from routine daily activities like cooking – like this family in Timor-Leste.

Is it possible to have both of these things? To be happy and feel our lives are meaningful? Or are the two increasingly mutually exclusive? As our societies achieve ever-rising levels of wealth and comfort, do we automatically become more individualistic, less compelled to make the sacrifices that are associated with living more meaningfully? We increasingly seek happiness by giving ourselves what we want in the present moment – buying nice things, watching Netflix and getting Facebook ‘likes’. We don’t spend so much time anymore doing things that give us meaning by transcending the self – investing in our communities, thinking deeply about the world around us and helping other people.

The research shows there’s always a bit of a trade off – you can’t have perfect happiness and a maximally meaningful life at the same time. But in western countries at least, those who live more meaningful lives generally do also report greater happiness levels. It makes intuitive sense that if we feel our lives are lacking in meaning, our happiness is limited too. The difference is that in poor countries, no matter how meaningful people may feel their lives are, they are still bound by their poverty – it concretely limits their happiness.

A woman chopping food for pigs outside Dili, Timor-Leste.

It’s not the ability to buy expensive consumer items that makes us happier than people in poor countries. It’s the ability to make basic choices about how we live our lives, the ability to access medical care if we need it, the freedom from worry about dying in childbirth or not being able to afford to send your kids to school. Personal wealth beyond a certain level doesn’t make us all that much happier, but access to collective wealth that safeguards our health and ensures we have a certain minimum standard of living really does make our lives much happier.

The irony is that when we humans are freed from the constraints of poverty, we find more trivial things to worry about. We do ‘sweat the small stuff’. We might be much happier on a relative scale, but we don’t always take the time to appreciate what we have – and it doesn’t automatically make us content with our lives. This is the human condition – to always want to make our lives better – and is part of us regardless of whether we’re rich or poor.

Apart from just being factually wrong, there’s another problem with the ‘poor but happy’ thing. As shown by this infographic, people from wealthy countries have a tendency to simplify poverty by either romanticising it as a noble, joyful and unmaterialistic state or alternatively to view poverty with pity, reducing poor countries, and even whole continents in the case of Africa, to one helpless, homogenous mass of suffering, completely dependent on rich people and countries for salvation (e.g. the Band Aid song Do They Know It’s Christmas was recently re-released for it’s 30th anniversary despite its ludicrous lyrics).

But in positioning people in poor countries as either above us (romanticising) or below us (pitying) we avoid having to acknowledge them as our equals, who are in poverty purely because of the terrifyingly random unfairness of life. We are actually distancing ourselves from them, positioning them as ‘the other’ rather than genuinely empathising with and respecting them. We’re airbrushing out the complexities and contradictions that ultimately make us all human, whether wealthy or poor (for more on this, see this great interview with Katherine Boo in Guernica).

A family living outside of Dili, Timor-Leste.

Negotiating the wrenching inequality of our planet obviously requires that we distance ourselves at a certain point otherwise we’d live every moment in an abyss of misery and despair. If you don’t have to live in poverty and you have the luxury of thinking about other things, then you will of course find ways to do this. It’s probably only natural that we try to find simplistic narratives that allow us to sit with poverty more comfortably, and to accept it as somehow ok. I think this is our brains trying to wriggle away from the guilt that we feel about our own privilege and wealth.

But it’s dangerous thinking, because if poor people are really ‘happy’ – if they are content with their lives as they are – then we don’t need to do anything about global poverty. Alternatively, if we put people in the ‘pity’ box, all we need to do is donate a little bit of money occasionally and we’ve done our bit and can forget about this whole troubling poverty thing.

I don’t doubt I’m equally guilty of thinking about developing countries in weird and patronising ways at times. So I’m not trying to lecture. But I think we have to try and look poverty in the eye honestly, without trying to invent any conscience-saving fairy-tales. If we can learn to do this, I think we stand a better chance of building honest and sincere connections with our fellow global citizens. And as a result, maybe we’ll understand their struggles a little better, and maybe we’ll be more motivated to ask them what we can do to help. And we’ll try harder and care more. Not out of pity but out of respect.

A little girl helping her family to crush and collect cans for recycling in Timor-Leste.